Thanks to the pervasiveness of Internet culture, most of us are aware of the phenomenon colloquially known as “Sunday scaries.” UrbanDictionary.com, an august authority on such matters, defines the term thusly:

Thanks to the pervasiveness of Internet culture, most of us are aware of the phenomenon colloquially known as “Sunday scaries.” UrbanDictionary.com, an august authority on such matters, defines the term thusly:

The feeling you have after a long week of work followed by a Saturday full of binge drinking when Sunday hits – you question your entire existence. Typically characterized by laying [sic] in bed all day and both regretting past decisions and questioning your seemingly non-existent future. Thoughts like “I’m going to die alone” and “Will I ever get a job that I actually enjoy?” consume you for the entire day while you’re battling a hangover.

Scary, indeed. And, hangover or no, Sunday is a day of heightened and pronounced anxiety for many.

Despite the recent coinage of the term, what the “Sunday scaries” describes is not an unprecedented era-defining collective experience of dreadful emptiness that emerges uniquely from the potent synergism of postmodern ennui, online everything, and “late-stage capitalism. ”Sunday scaries”—or something very much like it— is a phenomenon that was recognised by psychologists long before the invention of the viral meme.

A literary portrait of the “Sunday scaries”

I should note that my own introduction to what we now call “Sunday scaries” came from neither Instagram nor psychology but from literature. A good novel has as much to say about the psychology of its age as the most straightforward of psychology texts.

In his influential 1978 gay coming-of-age novel Dancer from the Dance, Andrew Holleran’s protagonist is the beautiful yet tragic figure of Anthony Malone. His name can be seen as an aptronym: A. Malone, or “am alone.” At the beginning of the novel, Malone is a twentysomething latent homosexual and corporate lawyer who lives and works in Washington, D.C. Despite the fact that he enjoys all of the trappings of a successful adult life, Malone experiences a terrible and baffling emptiness, which plagues him most excruciatingly on Sunday.

The gloom he felt … was nothing, however, compared to the terrifying loneliness that assaulted him on Sunday evening around eight o’clock; for then he had spent the whole day by himself, or driving around shopping for antiques with a fellow bachelor, and as he sat in his room looking down into the beautiful garden…he felt himself so utterly alone, he could not imagine anyone being sadder.

Tears came to his eyes as he sat there. This day, Sunday, was his favorite of the week; this day, Sunday, a family always spent together in the evening as they came home from their various errands for a cold supper and the perusal of the Sunday paper. This day, Sunday, the softest, most human, tenderest time, found him sitting bolt upright at his little desk by the window, hearing around his ears the beating of wings—the invisible birds assaulting him, beating the air about him with their accusing presence. He was alone like Prometheus chained to his rock. Tomorrow the rush of men, all working for a living, would drown him; but now, at this moment, in this soft green twilight, this soft green Sunday evening, when the heart of the world seemed to lie beating in the palm of his hand, he sat in that huge house upstairs terrified that he would never live.

He resolved to do anything to avoid solitude at this particular moment—which he regarded with the same fear an insomniac does the hour he must go to bed.

The passage vividly demonstrates the significance of Sunday to “Sunday scaries.” Biblically, the seventh day, Sunday, is the one day each week when we are called to honor God before the world. In more secular terms, that day has y become reserved for contemplation of the deeper mysteries and for communion with loved ones, to the neglect of one’s usual cares and concerns. To the extent that we are alienated from “God” or, transcendent meaning, we are especially vulnerable to dread, which rushes in to fill the void.

Crucially, the dreadful emptiness, boredom, or dissatisfaction one may feel on Sunday is not absent on the other days of the week. It just so happens that there is sufficient distraction available on those days to screen it out.

Holleran’s Malone resolves to do anything to avoid solitude on Sunday. That is to say, he resolves to do anything to avoid conscious awareness of the emptiness, hollowness, and meaninglessness that underlie his outwardly rich and successful life.

Insights from “The Third Viennese School of Psychotherapy”

Insights from “The Third Viennese School of Psychotherapy”

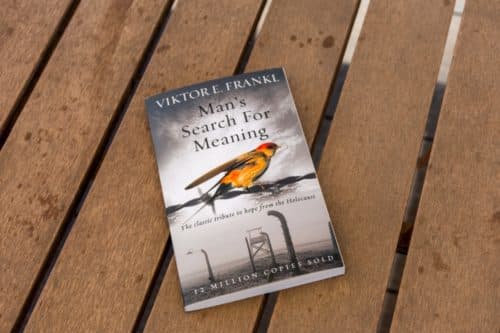

Perhaps no other individual has made a greater contribution to the psychological understanding of meaning—and of meaninglessness—than Viktor E. Frankl. An Austrian psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, Frankl (1905–1997) published the English translation of his reflections on life inside several Nazi concentration camps—1959’s Man’s Search for Meaning—to international acclaim. Based on the insights he harvested from his harrowing experiences, Frankl founded his own school of psychotherapy known as “The Third Viennese School of Psychotherapy,” after Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis and Alfred Adler’s Individual Psychology. Frankl gave the name Logotherapy (or “meaning” therapy) to his approach.

In the course of his meditations on the centrality of meaning to human survival and prosperity, Frankl provided what may have been the first psychological formulation of what social media influencers would later call the “Sunday scaries.” In Man’s Search for Meaning, Frankl writes:

Let us consider, for instance, “Sunday neurosis,” that kind of depression which afflicts people who become aware of the lack of content in their lives when the rush of the busy week is over and the void within themselves becomes manifest. Not a few cases of suicide can be traced back to this existential vacuum. Such widespread phenomena as depression, aggression and addiction are not understandable unless we recognize the existential vacuum underlying them. This is also true of the crises of pensioners and aging people.

Moreover, there are various masks and guises under which the existential vacuum appears. Sometimes the frustrated will to meaning is vicariously compensated for by a will to power, including the most primitive form of the will to power, the will to money. In other cases, the place of frustrated will to meaning is taken by the will to pleasure. That is why existential frustration often eventuates in sexual compensation. We can observe in such cases that the sexual libido becomes rampant in the existential vacuum.

The existential vacuum is a widespread phenomenon of the twentieth century. This is understandable; it may be due to a twofold loss which man has had to undergo since he became a truly human being. At the beginning of human history, man lost some of the basic animal instincts in which an animal’s behavior is embedded and by which it is secured. Such security, like Paradise, is closed to man forever; man has to make choices. In addition to this, however, man has suffered another loss in his more recent development inasmuch as the traditions which buttressed his behavior are now rapidly diminishing. No instinct tells him what he has to do, and no tradition tells him what he ought to do; sometimes he does not even know what he wishes to do. Instead, he either wishes to do what other people do (conformism) or he does what other people wish him to do (totalitarianism).

The existential vacuum manifests itself mainly in a state of boredom….And these problems are growing increasingly crucial, for progressive automation will probably lead to an enormous increase in the leisure hours available to the average worker. The pity of it is that many of these will not know what to do with all their newly acquired free time.

Frankl predicted that technological advancement and the accompanying increase in the automation of work—in conjunction with the effects of macrocosmic sociological trends such as disenchantment, secularization, scientism, postmodernism, and multiculturalism—would result in a widespread crisis of meaninglessness, with potentially disastrous consequences.

And, unfortunately, isn’t that exactly what we seem to have on our hands today?

Just a few grim data points will suffice to make the case. In the United States, the rate of suicide per 100,000 individuals increased from 10.4 in 2000 to 13.5 in 2020, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. The number of overdose deaths in the United States rose from 78,056 between 2019 and 2020 to 100,306 between 2020 and 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That is an increase of 28.5% in a single year. Hopelessness is clearly on the rise among Americans.

One also wonders if contemporary work culture has trended “24/7” to the precise degree that streamlined and automated working conditions have created too much of exactly what Frankl predicted: “an enormous increase in the leisure hours available to the average worker.” Too many leisure hours leave too much time for the “existential vacuum” to become manifest in conscious awareness, often painfully or threateningly. Our being available to work at all times—and work being accessible to us at all times—is arguably the “perfect” means of drowning out the howl of Frankl’s existential vacuum. The more the traditional workweek becomes “diffuse,” such that work now at least partially occupies all of our time, the less any awareness of the existential vacuum threatens to become so keen as to be unignorable.

How do we find meaning in our lives?

Luckily, we are not doomed to meaninglessness. Frankl suggested that there are three primary ways of discovering or creating meaning in our lives:

According to logotherapy, we can discover this meaning in life in three different ways: (1) by creating a work or doing a deed; (2) by experiencing something or encountering someone; and (3) by the attitude we take toward unavoidable suffering.

First, we can create a work or do a deed. In order to grant meaning, the work or deed in question cannot be any old job but must rise to the level of what might be described as a calling or vocation. The work itself can be as humble as you like—one need not hold high office to qualify—so long as it genuinely occurs to you as a calling or vocation. Crucially, the work or deed must be something whose purpose is larger than oneself.

Second, we can experience something or encounter someone. With respect to “experiencing something,” Frankl suggests that this “something” is somewhere in the neighborhood of goodness, truth, and beauty. These are the great ideals, nobler and loftier than mundane concerns. We could devote our personal lives to the cultivation of spiritual or mystical consciousness, to the appreciation or creation of aesthetic sublimity, or to the pursuit of universal truth.

With regard to “encountering someone,” Frankl warns that the ordinary approach to relationships will not suffice. Where the conventional wisdom says you cannot love another person unless and until you understand him, the meaning-granting approach says you cannot understand another person unless and until you love him. In this formulation of human connection and intimacy, the decision to love is itself a radical act.

Third, we can choose our attitude in the face of inevitable suffering. Frankl called the ability to choose one’s attitude in any given circumstance “the last of human freedoms.” Through our ability to face unavoidable suffering with an attitude of our own conscious choosing, we can transform tragedy into an achievement of the human spirit.

In conclusion

I must admit, I was rather surprised by the popular definition of “Sunday scaries,” as exemplified by UrbanDictionary.com. I had previously considered “Sunday scaries” less to mean painful awareness of emptiness on Sunday and more to mean anxiety about the impending arrival of Monday and the workweek to follow. But the two conceptualizations have more in common than initially seems. To the degree that one is not armed with a sense of meaning or purpose that transcends the mundanity of office buildings, strip malls, prestige television, and bitterly ironic Internet memes, the slings and arrows of Monday must appear very scary, indeed.

As we pursue transcendent meaning, Frankl reminds us that we should not ask, “What is the meaning of life?” but to remember that it is life that asks us, “What is the meaning of you?” Life may not provide a one-size-fits-all, tailor-made meaning or purpose for us to enjoy, but it does provide innumerable opportunities—in the form of potential acts, relationships, and unavoidable sufferings—to create individual meaning for ourselves. And we must have meaning as surely as we must have air.

Here, one final time is Frankl in his own words:

As each situation in life represents a challenge to man and presents a problem for him to solve, the question of the meaning of life may actually be reversed. Ultimately, man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather he must recognize that it is he who is asked. In a word, each man is questioned by life; and he can only answer to life by answering for his own life; to life he can only respond by being responsible.

Contact us today to schedule a complimentary 15-minute phone consultation or to book an appointment.

I strive to create a safe, comfortable, and supportive environment for individuals who are confronting issues related to adjustment, anxiety, depression, grief, stress, relationships, and trauma. I specialize in helping individuals who find themselves caught in repetitive patterns of less-than-effective coping and bewildering self-defeat. Call or message today to schedule your free phone consultation or arrange your first appointment.